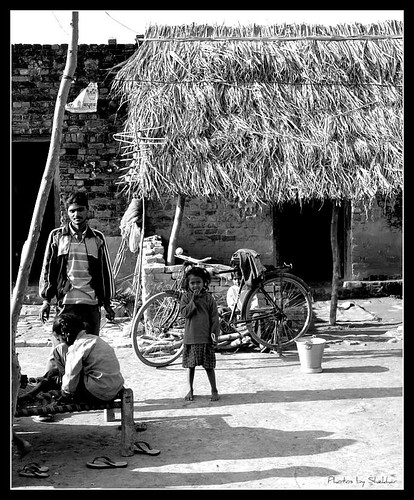

It is a still, dusty afternoon in Haiken punctuated by the sounds of children playing and women calling to each other as they return home carrying loads of water or firewood on their heads. At one end of the village sits an old weathered church on a raised level looking down at the community. In its shadow sits a humble mud and bamboo teashop. Kaisei Kipgen trudges up the stony path to it with a bag of fresh bread and snacks. His wife Nemmeng is rinsing out the cups in a basin of hot water. The stream of customers to their little teashop will begin soon. Their grandchildren run in and out of the shop; Robert, eight years old, asks for biscuits to pacify his younger cousins. It is an intimate, cosy place, its cool dark interiors and roughly hewn benches inviting conversation, banter, and gossip over endless cups of tea. To Nemmeng and Kaisei, a couple in their sixties, the shop is where they work and it is also their home: “we end up living and sleeping here, we feel comfortable here.”

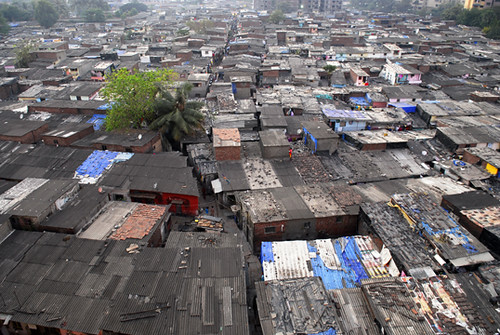

To Kaisei and Nemmeng ‘home’ has been a painful memory till recently. As they talk about their real home they stare into the middle distance watching the movie of their lives playing out, their memories still sharp with details. Kaisei was the chief of a Kuki village called KMollen in Ukhrul district on the border of present-day Myanmar. “Numbered pillars have been erected on the Indian border with Myanmar and pillars numbered 116 to 120, five pillars in all, were erected on my lands when I was a young man” he says. When the Kuki-Naga ethnic conflict of the early 1990s erupted Nemmeng and Kaisei were forced to flee their village leaving behind everything they owned including their paddy fields and the 300 tins of mustard oil and food-grains they had saved and stocked. Impoverished and stripped of everything they owned, the couple started all over again, but this time in their forties. They had six children to provide for so. Kaisei returned to the fields and Nemmeng took care of the family as she always had.

Nemmeng runs her hands over the two strands of amber beads around her neck; they have an arresting glow even though she has worn them for decades. Forty four years ago Kaisei brought her the central and biggest bead, the Khipi Chang or King Bead, when he asked for her hand in marriage. With time, and as Nemmeng rose in status as the wife of the chief, more beads joined the Khipi Chang. The beads are a source of pride to Nemmeng and they are a sign of the respect and status she continues to enjoy.

Nemmeng brings Kaisei his tea. She shuffles around the shop looking for his cigarettes. She gives him one and tucks the packet back in the folds of her ponve. Kaisei looks quite regal as he lights up. He blows out a stream of smoke, his eyes tear up and he coughs. He looks at her through the smoke, cough, tears and says: October 24, 1964. Every day since that day has been the best day of my life. Thats the day I brought my Nemmeng home.

Labels:

AGE OLD LIFE,

MANIPUR,

NEMMENG,

SEPIA,

TRIBES